Franco-Flemish double-manual harpsichord,

![]()

Louis XV’s Golden

Harpsichord?

Blanchet, Huet and Boucher attributions - certainties, ifs, maybes and buts!

![]()

![]()

What do we know with

certainty

about

this instrument and its decoration?

What we know about the construction of the instrument with certainty:

1. It was made in Antwerp in 1617 as a standard ‘transposing’ double-manual harpsichord with two keyboards separated by a fourth in pitch and with doubled strings for the eb/g# notes.

2. It was altered at an unknown date between 1617 and 1750 to give it a compass with 53 notes (probably from G1/B1 to d3). It is at least highly likely that the keyboards were aligned in the usual way at this stage in order to give the two keyboards the same compass and, and that keylevers for c#3 and d3 were made. If an extra string were added at this stage and space was made a both ends of the keyboard by reducing the thickness of the keyblocks and the whole keyboard were shifted down a semitone, then the length of the new added string for c2, for example, would be almost the same as the length of the original c2 and the pitch of the instrument as a whole would have remained, effectively, unchanged. Such an operation would have achieved the extra space required for the top natural d3 and, at the same time, would have maintained the pitch of the instrument and avoided the so-called 'van Blankenburg' problem. Three of the four registers from this altered state have survived and they all have the same additions at the bass ends and the same additions at the treble ends. The identical additions at the two ends of the registers are crucial to the determination of the compass and disposition of the intermediate states, including the second state with a G1/B1 to d3 compass.

3. Although the time of the insertion of the new early Ioannes Ruckers soundboard rosette is conjecture, we know with certainty that the whole instrument was extensively altered in Paris in 1750 by François Étienne Blanchet, harpsichord maker to King Louis XV. Blanchet widened the instrument on the bass side by extending the case, the soundboard and the bridges, he made new keyboards (lost in the 1786 alteration), he made new jacks most of which still survive, and he extended the bass ends of the registers which still exist from an earlier state (no. 2 above). It is virtually a certainty that, at this stage, the compass was F1 to d3. We know with certainty that King Louis XV was Blanchet’s most important client by far the majority of the harpsichords inventoried among the collection of Louis XV in 1786 were either by Blanchet or they had been given a ravalement by Blanchet.[1]

4. Almost certainly at the same as it was given the ravalement by François Étienne Blanchet, it was given a genuine Ruckers soundboard rosette to counterfeit it as an instrument by Ioannes Ruckers - the Stradivarius of the harpsichord-making world. In so doing Blanchet would have increased the commercial value of the instrument by roughly 10-fold. All that was required to do this was to cannibalise the soundboard rosette from a, by then, worthless Ioannes Ruckers virginal!

5. The instrument was altered in 1786, probably by Jacques Barberini (who left his calling card on the 1786 baseboard inside the instrument) and Nicolas Hoffman whose signature and the date 1786 survives on the keywell side of the lower belly rail. 1786 is the period during the reign of Louis XVI when the harpsichord as a serious instrument for music making was facing serious competition from the pianoforte. Barberini and Hoffman widened the case, soundboard and bridges to increase the treble compass of the instrument to f3 so that it could play all of the contemporary music, made totally new keyboards (which survive) extended the registers on the treble end (these survive) and there is strong evidence that one or both of these keyboard instrument makers installed a fourth ‘peau de buffle’ register and a genouillère to give the instrument the ‘expressive’ capabilities to help it to compete with the piano. The keyboards, with ivory naturals and ebony sharps are out-of-keeping with normal French black ebony keyboards and are almost certainly by Jacques Barberini who is known to have dealt in a flourishing trade in Paris in English square pianos and harpsichords. These English instruments always had white keyboards, and Barberini seems to have tried to give the instrument the same style of white keyboards like those he sold. The stand, which shows no signs of ever having been extended, must date from the treble case extension in the period around 1786.

6. Alterations were made by Louis Tomasini in Paris in 1889 (probably minor alterations as Tomasini is known for his very conservative restorations), by Arnold Dolmetsch in England (addition of stifle bars under the soundboard, removal of the soundboard painting which was replaced with Mabel Dolmetsch’s painting, the removal of the genouillère and the disastrous thick coat of linseed-oil varnish to the case and soundboard) in about 1915, and by Roberto de Regina in Buenos Aires (removal of the 1786 baseboard, replacement of the 1786 wrestplank, nuts and tuning pins, and the replacement of the bass section of the 8' hitchpin rail along with the bass back-pins of the 8' bridge). Except for making any attributions more difficult, these late alterations obviously have nothing to do with the eighteenth-century history of the instrument and its decoration.

What we know about the decoration of the instrument with certainty:

1. There is an exact correlation between the dated parts of the instrument, the alterations to the case, and the decorations. This makes the dating of the decorations definite and precise. The structural alterations indicate that the majority of the instrument was totally redecorated in 1750 at the time of the Blanchet ravalement, and that there were then minor alterations and additions to the treble-side decorations following the treble extension of the compass in 1786. Some modern additions were carried out in the period between 1889 and the Exposition Universelle, and the disastrous restoration by Arnold Dolmetsch in about 1915.

2.

The recent UV light, incident grazing light and the pigment and medium analyses carried out under the

Paris restorers (May, 2018)

indicate that the decorative artists

who carried out the figure paintings and the ornaments were both highly trained

and highly skilled in their craft. Both

the skill with which these artists laid down the foundation layers, and the

systematic way that they then layered on the paint to create form, depth and

shade

indicate that they were certainly artists at the very top ranks of their

community. It is unlikely therefore

that they were pupils of another master, or that they belonged to the school of

- or the circle of - one of the pre-eminent masters of the mid-eighteenth-century

Parisian school. They were clearly

masters in their own right.

There is no evidence from

the pigment and medium and analyses that any of the materials used in the

decoration of the instrument are incompatible with the date 1750 or with the

palette of an eighteenth-century Parisian artist. All of the pigments and

media found in these analyses were in common use in 1750 and there is no

question of the paintings being later, nor of them being in a later ‘pastiche’

style of the later 19th-century romantic painters. The pigment and medium analyses are also

totally consistent with the results, obtained mostly using X-ray fluorescence

analyses, of the Boucher paintings analysed by the National Gallery of Art in

Washington, D.C. and provided to me by Juriko Jackall (formerly National

Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C, and now at the Wallace Collection, London) and by

Leila Packer, Wallace Collection, London.

3. The Boucher white doves recur six times on the outside of the lid and lid flap:

The Boucher white doves are a recurring element of Boucher's stock-in-trade. The badly-damaged images above are from the painting on the top of the lid of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. This, along with the paintings on most of the case of the instrument, was once covered in an intransigent layer of thick, insoluble linseed-oil varnish. The removal of this varnish caused some considerable damage to these figures, but their authorship is still quite clear (see below). The paintings above have yet to be restored.

![]()

A Boucher white dove: a detail from Mars and Venus surprised by Vulcan, 1754, Wallace Collection, P438.

|

More Boucher white doves, a detail from Boucher's Les forges de Vulcain, 1757, The Louvre, Inv. 2707 bis. |

Just as with the faces of his human figures, Boucher paints the faces of his white doves with a distinctly un-natural appearance. The two paintings above, both by Boucher, show the heads of the doves from oil paintings which, although delicately and elegantly poised, are quite un-natural. The shape of the beak and the position of the eyes on the head are drawn with an almost child-like naivety. This is exactly the same distortion of the features as that is seen in the paintings of the faces of the white doves on the outside of the lid of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord above.

4. The main figures on the outside of the lid flap (Diana, Cupid and their attributes), on the main portion of the lid above the soundboard (Juno, Flora, Cupid and a reclining nude) are all in the style of François Boucher (see below). UV analysis of the paint shows that the painting of Diana, Flora and Juno all use the same pigments and technique, and were all painted at the same time and by the same person. However, the 'Triumph of Love' sequence on the front flap, the cheek, the bentside and the tail were, however, painted by a different artist (but at the same time as the figure paintings on the outside of the lid). The UV analysis as well a grazing light examination, shows that all of the painted figures on the instrument are by the same artist.

But the UV analysis shows further that the putti figures on the 'Triumph of

Love' on the case sides have

been very heavily re-touched. This retouching is so widespread and

involves all of the figures to such an extent that they presently display very

few of the usual features of

Boucher’s work (see below) and that this makes them look like pastiche.

The most serious feature of this retouching is that it

makes their attribution very confusing.

One of the most heavily re-touched paintings is that seen on the image of the

putto painted on the tail of the harpsichord:

The modern restoration of the ‘Putto in Triumph’ on the outside of the tail of

the instrument, photographed in normal light

(left) and the same figure photographed in UV light (right). Is that a

dolphin's or a lion's head to the putto's right? Why, in any case, does it

have a baseball bat in its mouth which then protrudes out over its back? What,

exactly, is meant to be portrayed underneath the far end of the baseball bat?

Is it a fish (dolphin?) tail, is it armour, or what exactly is being represented here?

This figure shows clearly the effect of the retouching in making an assessment

of the figure and an attribution of the painter of this scene extremely difficult.

The right-hand photograph indicates clearly the extent of the retouchings,

mostly all modern, to the figures painted around the outside of the case of the instrument.

Despite all of the re-touchings and alterations to this figure indicated here, the torch carried aloft by the putto has been relatively unretouched. This torch is

identical in technique and character to the stylised torches found in many of Boucher’s other

paintings.

The rest of the figures of the putti on the cheek and bentside of the harpsichord are

not usually as strongly re-touched as the figure on the harpsichord tail above, but the heavy

re-touchings do tend strongly to disguise their authorship. However, the UV analyses has also shown that

at least some of the faces and bodies of these figures have been left almost in

their original state without being

re-touched and repainted. Two largely-untouched figures are shown below:

The photographs above show the head of one of the figures taking target practice in the second scene (left) and head of the figure of the charioteer (right) in the last scene of the ‘Triumph of Love’, both on the bentside of the instrument. Although most of the bentside figures have been heavily re-painted, UV evidence shows that both of the figures in the photographs above have barely been re-touched either in historical times nor in modern times. The head and face of the figure on the left is particularly striking and is painted with a high degree of skill: the delicate modelling of the hair, the reflection of the light off the chest of the figure behind him onto his face, etc. There is even a small highlight on his right ear-lobe with light reflected off the other figure. Both of these un-retouched figures betray an artist of the highest level of skill. They also display many of the characteristic distortions painted into the faces of the putti in Boucher’s other paintings. As mentioned above, the UV analyses show further that all of the figures on the front fallboard, the cheek, bentside and tail were painted using the same pigments and technique as the rest of the figure paintings on the outside of the lid of the instrument. This means that all of the figure paintings including those of Diana, Flora, Juno, Cupid and the reclining figure near the tail of the lid are by the same artist who, as the evidence below shows, must surely have been François Boucher.

5. The UV analysis has shown a further number of important features of the image of carnal love to the right of the Flora/Juno/Cupid group on the top of the main lid section: 1) the general physiognomy of the reclining nude is identical to that of the red chalk Odalisque Blonde by Boucher in the Horwitz Collection in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (below). 2) the face of the reclining nude (middle below) has been altered in historical times soon after 1750 as indicated by the bright fluorescence, rather than the dark patches indicating more modern (but not, in this case, recent) re-touchings which absorb the UV light.

The photograph at the top shows the image of the reclining nude painted on the top of the main lid of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord after cleaning, but without any of the recent restoration of the painting which has happened on the bentside and spine. The photograph in the middle shows the identical image photographed in UV light. The lower photograph shows an image of the red chalk drawing of the 'Odalisque Blonde', 1742-43, by François Boucher from the Horwitz Collection at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

The

historical re-touchings in the middle image fluoresce brightly, whereas the

modern (c.1915?) re-touchings are seen as dark patches which reflect no UV light.

This shows that the basic physiognomy of the figure has been very little

altered in the course of its history, and that it is basically the identical figure

in the same pose as the red chalk version of the

'Odalisque Blonde' in

Boston, seen at the bottom.

However, as has been made clear by Alastair Laing, this pastel and the many

paintings of this same figure all pre-date by some considerable period, the

entry of Marie-Louise O'Murphy into the service of the French Court. So,

as initially painted this figure had nothing to do with Marie-Louise O'Murphy. My theory is that the face

which was initially painted on the figure on the harpsichord lid in 1750 would

have resembled the earlier Odalisque versions and the face seen above in the

Boston red-chalk image. But, since Marie-Louise O'Murphy had not yet arrived in Court

when the initial decoration was carried out in 1750, the initial painting of the

figure would have been identical to Boucher's chalk drawing. The body

of the figure

itself therefore has nothing to do with Marie-Louise O’Murphy since she arrived

in court only around 1753. It seems rather, in 1750, to have

represented nothing more than the contrast between carnal love and the divine love

represented by the figures

of Diana, Flora, Juno and Cupid painted elsewhere on the outside of the lid.

However, the UV image (above middle) shows that the face has later received a strong

re-painting, and that this re-painting was carried out in historical times as

indicated by the light-coloured fluorescence.

In my view this was to make the face

of the figure resemble that of Marie-Louise O’Murphy who joined the King’s

service as a petite maitresse in 1753.

If this is so it would date the re-painting of the face to 1753 or a year

or so afterwards. It is also a very strong indication that the figure was

altered to conform to the entry of Marie-Louise into the French Court and,

indeed, that the instrument itself had, since 1750, been used for music-making

in the Court, whether by Mme. de Pompadour, Jean-Philippe Rameau, the

Mondonvilles or any of the many other Court musicians.

6.

There

is a number of correlations and precedents of various aspects of the decoration on the

Franco-flemish harpsichord with previous and later works by François Boucher.

1) There are two Boucher paintings showing a forge scene with putti making and sharpening

arrows. Both of these Boucher paintings

are very similar to the forge scene painted on the fall board of the harpsichord.

These indicate a strong connection between Boucher and the badly-damaged painting on the fall-board of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord.

|

Les amours forgerons From the Sale Catalogue, Lot 40, HÔTEL DES VENTES DE NEUILLY, 19-12-2013, Paris. |

Les amours forgerons, by Francoise Boucher, c.1737. From: Francois Boucher. A loan exhibition for the benefit of the New York Botanical Gardens, November 12 - December 19, 1980, (Wildenstein, New York, 1980) No. 30, p. 68. |

The two paintings at the top above

are by Boucher, both showing putti making

arrows at a forge. Below these is an image of what remains of the painting of a forge scene on the

front fall-board of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. Even though little remains of this part of the painting on the harpsichord, we

can see a putto putting an arrow-head into the forge on the left, a putto

hammering an arrow head on an anvil in the centre and a third putto holding the arrow in

place on the anvil using

blacksmith’s tongs on the right. The figures in the lower photograph have

(obviously) not yet been restored but show that the faces of the outer figures are extremely

well painted and that they are in the style usual for Boucher with the same

typical facial distortions. These are clear precedents to the paintings on

the front fallboard and indicate that they are all by Boucher.

7. Another scene found on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord and also found among Boucher’s attributed oeuvre is that of the kissing putti in monochrome blue in the middle of the bentside. The figures in the two photographs below are almost identical: the one on the left is seen in a silhouette carved in the fountain in the middle of the 1749 painting of A Pastoral of a Couple near a Fountain by François Boucher in the Wallace Collection, London (No. P482), and this is compared with the almost identical figures seen in the cartouche in middle of the harpsichord bentside (right). The nearness in date of the two (1749 - left, and 1750 - right) is a further indication that the two images are related.

The photographs above show

a detail from the grey monochrome (a fountain) in Boucher’s Autumn Pastoral (No. P482) in

the

Wallace Collection,

London (left) compared with the (heavily-retouched) blue monochrome of kissing

cupids painted in the middle of the harpsichord bentside (right).

The

Wallace Collection image is probably a good guide to how the

harpsichord image should be re-touched near the bottom of the oval cartouche

where this part of the painting does not ‘read’ in the context of the rest of

the monochrome painting.

8. The head of Flora painted near the middle of the main part of the lid of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord can be seen in a virtually identical image to that seen in the 1753 Boucher painting of The Rising of the Sun and again in The Setting of the Sun (not illustrated here), both in the Wallace Collection, London (P485 and P486, respectively). In the Wallace Collection painting of The Rising of the Sun Apollo is pointing with the index finger of his left hand at one of the Titan Water nymphs who has been accepted as representing Mme de Pompadour (see below).

The Rising of the Sun, by François Boucher, Paris, 1753, The

Wallace Collection, London, Inv. P485.

The companion 1753 painting by Boucher in the

Wallace Collection The Setting

of the Sun (P486) also features an image of this same head (see below left). The two Wallace Collection paintings are known to have been commissioned by Mme de Pompadour from

Boucher.[2] But as a tribute to his patroness, Boucher painted the face of de

Pompadour onto the figure of the Titan Water Nymph Téthys who appears in both paintings. Here, Apollo is seen pointing with the index finger of his left hand

directly at Téthys and, by implication, to his patroness Mme de Pompadour. Mme de Pompadour commissioned this

painting as a cartoon for the Gobelin tapestry firm, so presumably she is also

represented on the Gobelin tapestry as well. The same head and face (although in mirror

reflection) also occurs on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord (below right):

The head of Téthys from The

Setting of the Sun, 1752, Wallace Collection, London, P486, (left - rotated and with a mirror

reflection), the head of Téthys from The Rising of the Sun (centre) also with a rotation and a mirror

reflection from the Wallace Collection, London, P485 (scholars at the Wallace

Collection claim that both of these are, in fact, portraits of Mme de Pompadour), and the head of Flora from the painting of Flora, Juno and Cupid on

the outside of the main lid of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord (right).

All of these were painted within 3 years of one another and so all of

them appear to be portraits of Mme de Pompadour!

7. The head of Diana on the outside of the lid flap showing Diana, Cupid and their attributes shows a strong resemblance to the heads on the figures above and to the two images of Téthys in Wallace Collection paintings by François Boucher. It therefore appears that Mme de Pompadour commissioned the painting of the figures on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord and that she figures as Diana on the outside of the lid flap, and as Flora on the outside of the main lid. This helps to confirm the long-held suspicion that Mme de Pompadour commissioned the ravalement of the harpsichord by François Étienne Blanchet, harpsichord maker to King Louis XV, the painting of the figures on the harpsichord by François Boucher, painter to King Louis XV, and the painting of the decorations on the harpsichord by Christophe II Huet (1700 - 1759), who carried out a number of room decorations for Mme de Pompadour.

These photographs show a detail of the head of

Diana from the outside of the

lid flap photographed in normal light (left) and in UV light (right). This shows that this image has been very

little retouched during the past 270 years:

the bright patches fluorescing green here show some small retouchings made to the

face during the historical period around 1750 to 1786, and dark patches show

retouchings made during the modern period probably between 1887 to 1926. These are both minor and do not distort the general

appearance of the face.

The image on the left is therefore almost un-retouched and so represents almost

exactly the

work of the artist as he left it in 1750.

This image is very similar to the face in a number of paintings of Mme

de Pompadour by François Boucher and others. For example, compare the

images above with that of Mme de Pompadour (below). I have chosen a

portrait not by Boucher in order to underline the similarity of the face

on Diana to the features of the face of Mme de Pompadour, regardless of who

painted her:

Detail of the Portrait en pied de la marquise de Pompadour, 1752-3, Musée du Louvre, Paris, Inv. No. 27614, by Maurice Quentin de la Tour (mirror reversal).

The similarity between the de la Tour portrait and the image of Diana above is

striking. At

this time Mme de Pompadour was avidly commissioning works by many artists,

including Boucher and de la Tour, as well as the many other musicians, writers, artists and

craftsmen active in the French Court. She clearly did this in order to perpetuate her

memory as a woman of intellect, refinement and taste. This image, and indeed the re-building and decoration of the whole

harpsichord, seems to be yet another example of Mme de Pompadour’s attempts to

create and establish her role in the French Court.

Clearly Boucher, when decorating this instrument, gave Pompadour, the Grand Maîtresse of Louis XV, the

role of the Queen of Love in Louis’s Court, although she could not hold the

title of Queen of the Realm.

9. Usually, in both England and France, the spine side of a harpsichord was left undecorated and in some cases even left as plain, untreated, raw wood. The reason for this is because 18th-century furniture in both England and France was normally pushed up against the walls of the rooms in which the furniture was kept. There was no more reason to decorate the spine side of a harpsichord than there was to decorate the back of a bookcase or of a wardrobe. However, some particularly highly-decorated English harpsichords have a spine decorated with veneer and stringing and even marquetry, and were meant to be the centre-piece of a room full of furniture otherwise positioned against the walls. The Franco-Flemish harpsichord is the only known French harpsichord with a decorated spine:[3]

The spine side of the

Franco-Flemish harpsichord totally decorated by Christophe II Huet.

This is the only known French harpsichord by any

eighteenth-century Parisian maker with a decorated spine. This

singular feature almost certainly derives from the fact that it was a very

special piece commissioned by the French Court and intended by Pompadour to be

the centrepiece of one of the grand rooms at Versailles.

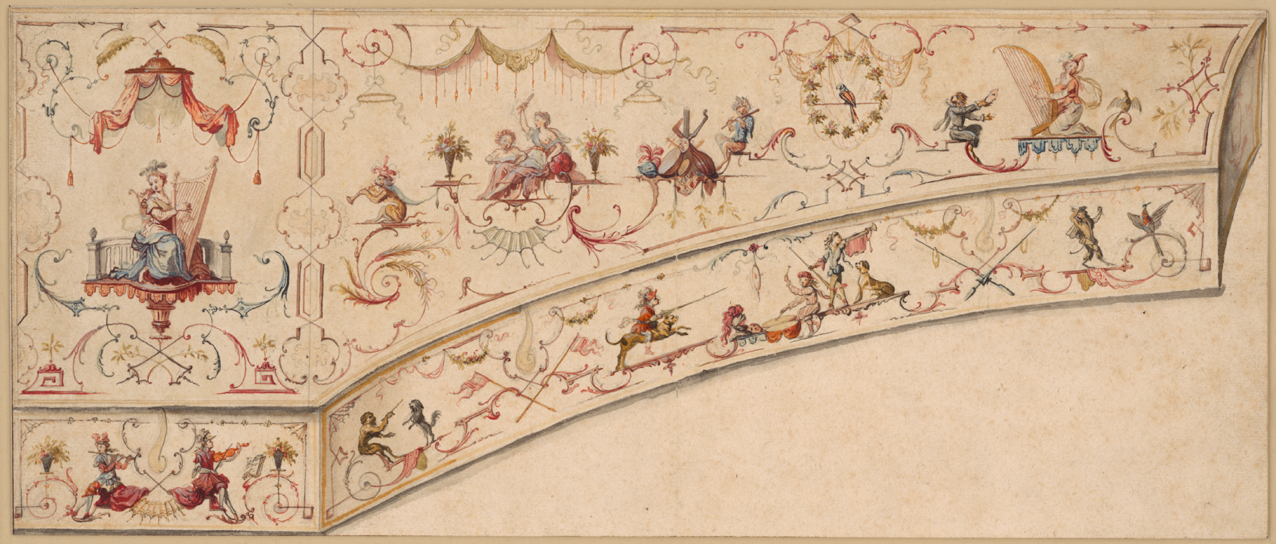

Three of Huet's designs for harpsichord decorations. These are, like the decoration of the Thoiry Blanchet harpsichord discussed below, all entirely by Huet, with no additional figure paintings by Boucher or anyone else. Note the almost mathematically-perfect spirals, the 'geometrical' arabesques, the 'shell' fans, the pendulous swags (both naturalistic and geometrical), the trophies, the naturalistic and fantastical musical instruments, etc. These are all features of the Huet decoration that are in common with the decoration of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord above, and with even more features that these three designs above have in common with the decoration of the Thoiry Blanchet double-manual harpsichord discussed below.

I am extremely grateful to Florence Gétreau for pointing out these Huet harpsichord decorations and for supplying me with these images.

10. There are many references in the literature and in fact to examples of co-operation between the four players in common to this instrument: François Étienne Blanchet, Christophe II Huet, François Boucher and Madame de Pompadour:

-

Blanchet - Huet connection: François Étienne Blanchet is the maker of the 1733 double-manual harpsichord decorated by Christophe II Huet and located in the Château de Thoiry, Yvelines, France. This is now - other than the Franco-Flemish harpsichord under study here - the only harpsichord by Blanchet to retain its original jacks which have been used to make a definitive attribution of the ravalement to Blanchet. The fact that Huet decorated the Thoiry harpsichord, including probably even the stand, is proof that here is a very strong connection between Blanchet and Huet. It amounts, quite simply, to the fact that Christophe II Huet decorated at least some of Blanchet's harpsichords and, by implication, the instruments that Blanchet had mis à ravalement.

The decoration by Christophe II Huet of the cheek (left) and a dancing crane on the bentside (right) of the harpsichord at Chateau Thoiry by François Étienne Blanchet, 1733.

This demonstrates Huet's extraordinary ability to paint birds of all types. He shows these full of life and in naturalistic poses. Huet also specialised in 'singeries' or scenes with monkeys in contemporary 18th-century dress carrying out normal human activities such as playing instruments, dancing, courting, painting, serving one another tea, archery, etc. But most importantly from the point of view of attributing the painter of the decorations on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord, the images above also display Huet's strange ornamental style in the decorations around the border of the harpsichord cheek on the left. It is the latter of these features that are so evident on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord, particularly on the spine (see the link at the left and the image and discussion above). These decorations are quite unlike those of any other artist and there can be no question that they were carried out on the Franco-Flemish harpsichord by anyone other than Christophe II Huet.

-

Blanchet - Louis XV connection: Although the title wasn't given to him until the mid 1750's (and therefore after Blanchet's ravalement of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord), François Étienne Blanchet spent much of his time working on the King's instruments at Versailles. A number of the instruments used at Court were by Blanchet or had been mis a ravalement by Blanchet. There is documentary evidence that Blanchet was asked to re-quill the instruments at Versailles as many as 3 or 4 times a year. There were at least 20 harpsichords at Versailles, so this must have meant a great deal of work for Blanchet and his assistants. There was clearly a very strong relationship between Blanchet and the Court and between Blanchet and Mme de Pompadour who organised all of Louis XV's domestic affairs such as the maintenance and, I would insist, on the commissioning of the making and ravalement of new instruments.

-

Boucher - Huet connection: Boucher worked with many other artists on artistic and decorative projects with painters such as Jean-Baptise Oudry (1686 - 1755), Claude III Audran (1658 - 1734) and Christophe II Huet. So it should be no surprise that the Franco-Flemish harpsichord was decorated by two painters, both of whom worked for the Court, and both of whom had collaborated together on other projects.

-

Pompadour - Huet connection: Christophe II Huet is known to have carried out many commissions for the French Court and in particular for Mme. de Pompadour. She commissioned him, for example, to carry out the decoration of some of the rooms in the Château Champs sur Marne which she rented and used as a temporary retreat from Court life at Versailles.

-

Boucher - Louis XV connection: Boucher received the accolade of Court Painter to Louis XV and was therefore the official painter for all of the many commissions from Louis himself and also from Mme. de Pompadour.

It is my view that all of these connections coincide simultaneously in this one instrument!

And what we don’t know

with certainty?

But with the ‘buts’!

1.

To date we unfortunately do not have

any documentary evidence that the instrument was commissioned for the French

Court by Mme de Pompadour. Evidence

for this could probably only be found through a search of the French archives -

particularly those relating to the Palace of Versailles in the period leading up

to 1750. However I, personally, have made

no attempt to search the archives for evidence of this instrument being given a

ravalement and being painted and decorated in 1750. Only a thorough search of the Court archives might confirm a

positive connection here.

But:

The strong connection of Blanchet,

and Boucher to the French Court and to

Mme de Pompadour makes the commissioning of this instrument at least highly

likely. Her image has been painted twice on the outside of the lid, and this adds to the

probability that it was commissioned by her for the pleasure of Louis XV.

2.

We

do not know with certainty when the face of the figure of the reclining nude on

the outside of the main lid was altered.

I can see no way now of being able to tie this date down with precision and

certainty. It is very unlikely that there is documentary evidence for this

small re-touching of the decoration of the harpsichord.

But:

The re-painting of the face of this figure ties in very well with the date of

the initial painting of the lid and with the date that Marie-Louise O’Murphy

came into the service of the King. This therefore strongly suggests that

the reclining nude is, indeed, Marie-Louise O'Murphy

![]()

The spine-side view of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord. Here we see the decoration of the spine side of the instrument - unique among all of the French 18th-century instruments in the world - with its bizarre decoration by Christophe II Huet. As mentioned above this is the only French eighteenth-century harpsichord known with a decorated spine - an indication of the role that it must have played when it was new and first commissioned. Also visible here on the outside of the lid are the Huet decorations surrounding the figure paintings, as well as the figure paintings themselves which have been attributed here to François Boucher. The stand, although totally out of fashion by 1786, is in perfect accord with the external decoration. This stand must date to the ravalement by Barberini and Hoffman, Paris in 1786, since it has never been widened to accommodate the larger case width resulting from the extension of the treble compass which happened at that date.

One of my former students, Lance Whitehead, has discovered that the two trophies of musical instruments are based on designs by the French Rococo painter Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684 - 1721). I am very grateful to him for supplying me with this information.

![]()

Conclusions:

In my opinion the ravalement and decoration of this instrument was commissioned to represent Mme de Pompadour’s artistic taste, but also, practically, to show off her ability as a musician to the rest of the French Court. I believe she was responsible for commissioning Blanchet to carry out the ravalement of the instrument, and I believe it was she who commissioned Boucher to carry out the figurative paintings on the outside of the lid, including two images of herself. She commissioned Christophe II Huet, who carried out a great number of commissions for her, to paint the decorations around the figure paintings. She was, after all, a pupil of the foremost French musicians and composers to the Court including Jean-Philippe Rameau, and she was a personal friend to both of the composer/musician Mondonvilles.

Many of the facts described above are certainties and the suppositions are all at least highly probable.

This harpsichord was something very special when it was commissioned

and when it was new. In addition to

everything else, it even had a decorated spine!

![]()

Portrait, Mme de Pompadour touchant un clavecin, Musée du Louvre, Inv. No. 21518, Francois Boucher, 1750.

Very beautiful!

But what is the date of this painting??? Ah, and what is the date of the ravalement of the Franco-Flemish harpsichord? And exactly which harpsichord is that in this amazing painting by Francois Boucher??

![]()

- Grant O’Brien, Edinburgh, July 2018 and November, 2018.